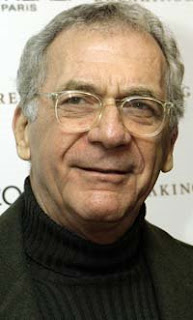

In the next few months, Romaine "Chip" Fitzgerald (above), the longest held political prisoner in American history, will have another parole hearing. Fitzgerald has been in prison since 1969. Some background: In early 1969, Fitzgerald, an 18-year-old resident of Compton, joined the local Los Angeles chapter of the Black Panthers, an African-American activist organization that is wrongly described as a "terrorist" group by its right-wing critics. Like so many young African Americans living in the inner cities, Fitzgerald was angered by the rampant police abuse and lack of opportunities in L.A. in the late 1960s. Joining the Panthers offered countless black teenagers and twentysomethings a productive outlet for their simmering frustrations.

In October '69, Fitzgerald was arrested -- along with some other friends -- following an altercation with a California Highway Patrol officer (who was under orders to "shoot to kill" all known Panthers). In the affray, the officer was shot and Fitzgerald fled the scene. The officer survived, the Los Angeles police arrested Fitzgerald, and he was not only convicted of shooting and wounding the Highway Patrol officer, he was also charged with a murder of a security guard at a Vons supermarket in Los Angeles. The evidence was flimsy, but Fitzgerald was locked away in the California prison system for almost forty years. Fitzgerald vehemently denies any involvement in the murder of the security guard.

With the passage of time, we have developed a deeper understanding of the turbulent years of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Keep in mind the backdrop of events surrounding Fitzgerald's arrest and conviction. Charles Dickens' words about "the best of times, the worst of times" certainly apply here. This period was characterized by war, polarization, crises at home, racial discord and a "law-and-order" crackdowns against all dissenting groups. Now, forty years later, we are able to put this difficult period in context. Many historians agree that the federal government -- in cooperation with local law enforcement agencies -- waged a systematic and unjust war against the Black Panthers across the country.

Chip Fitzgerald was but one of many people sucked into this chaotic maelstrom. In recent years, we have learned that other political prisoners who shared his same fate were innocent. Geronimo Pratt (right), a Vietnam Veteran and Black Panther, spent 27 years in prison for a crime he did not commit. He was eventually freed in 1997. In Louisiana, Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox -- two Black Panthers from New Orleans -- were serving time for armed robbery when they were charged with the 1972 stabbing of prison guard Brent Miller. Earlier this month, the Los Angeles Times ran a powerful story (May 3) that raised serious questions about their guilt. In fact, Miller's widow, Leontine Verrett, told the L.A. Times: "If I were on that jury, I don't think I would have convicted them."

Chip Fitzgerald was but one of many people sucked into this chaotic maelstrom. In recent years, we have learned that other political prisoners who shared his same fate were innocent. Geronimo Pratt (right), a Vietnam Veteran and Black Panther, spent 27 years in prison for a crime he did not commit. He was eventually freed in 1997. In Louisiana, Herman Wallace and Albert Woodfox -- two Black Panthers from New Orleans -- were serving time for armed robbery when they were charged with the 1972 stabbing of prison guard Brent Miller. Earlier this month, the Los Angeles Times ran a powerful story (May 3) that raised serious questions about their guilt. In fact, Miller's widow, Leontine Verrett, told the L.A. Times: "If I were on that jury, I don't think I would have convicted them."There are countless other Panthers who were the innocent victims of brutal repression. Add Chip Fitzgerald to that list. Having served almost forty years in prison and now approaching 60, his health is deteriorating and he is growing weaker and weaker. Last year, Fitzgerald issued a statement that accurately described the sorry state of America's prisons: "The prison system has mutated into a complex dysfunctional resource-wasting parasite of social control, political repression and revenge! Human beings are warehoused in these concrete and steel bunkers that destroy human sensibilities and the human spirit. Then following years of continuous antagonism and frustration at the hands of sadistic prison guards tortured souls are released on to an unsuspecting public to offend. There in is the cause and effect of an 80% recidivism rate."

The time is long overdue to Free Chip Fitzgerald. There are some things you can do: 1. Find out more about Chip by clicking here; you can also read a helpful Blog (from the Unapologetic Mexican) here on Fitzgerald. 2. Sign the petition to free Chip Fitzgerald by clicking here. 3. Write a letter to the parole board showing your support. The snail-mail address is:

Board of Parole Hearings

Post Office Box 4036

Sacramento, CA 95812-4036

Let's get Chip Fitzgerald out of prison. He does not belong in there. And let's end the brutal and costly war against the Black Panthers, waged by the federal government and local law enforcement authorities, once and for all. It has dragged on much too long.